Who’s in Your Backyard?

Edina’s attitudes towards low-income housing reveal larger issues.

Jada Lee (pictured) is a sophomore at Edina High School.

Edina’s reputation for being wealthy and educated is well-known throughout the Twin Cities. But while this reputation boosts our egos, its reality harbors classism, xenophobia, and a lack of diversity.

Progressive society has offered its hands to the underserved so that they may receive opportunities similar to those better-off. For example, affordable housing is meant to give underserved families the chance to live in excellent school districts, become skilled workers, and break away from poverty. But how far has Edina come to integrate low-income families into its exceptional schools and neighborhoods? Adults, as well as teenagers, need to have increased awareness about the lack of affordable housing in Edina, its root causes, and the opportunity to improve our society.

Segregation in Edina is grounded in history. From 1924 to 1948, the Country Club neighborhood ordained a “racially exclusive deed covenant,” in which non-Caucasians were legally barred from buying a house or living in the Country Club neighborhood, unless they were a domestic servant (Reinan, 2015). These exclusive covenants were nationally outlawed in 1948, but in reality, Edina continues to practice income and race-based segregation today.

In the summer of 2014, the Boisclair Corporation proposed a mixed-use development on 7200 France, featuring 32 affordable housing units in addition to 160 luxury apartments and retail space (Kaczke, 2014). Immediately, the project met strong disapproval from Edina residents living near the proposed development, expressed in over 200 furious emails to the Edina City Council and the presence of indignant residents at city council meetings.

Did income and race have anything to do with it?

Such a strong reaction from the Edina residents may very well be grounded in elitist views and racial stereotypes. While there is a long list of complaints, including unwanted density, increased traffic, and excess building height (Hankey, 2014), there are stronger arguments as to why these are just technical excuses to prevent affordable housing in Edina.

The Edina residents may very well be grounded in elitist views

First, although the project’s proposed density is greater than allowed by Edina building codes, the recently approved Aurora on France development—just a few blocks north of 7200 France—is double the maximum allowed density (Groessel, 2015). Also, a traffic study by Boisclair Corporation showed that France Avenue has “the capacity to add more cars” (Kaczke, 2014), so there would not be drastically increased traffic. Likewise, there are many luxury apartments being built in the Southdale area that are well above the maximum height allowed (Kaczke, 2014). Most importantly, the ongoing urbanization of the Southdale district provides evidence for its appeal to potential residents where they can live, work, and play – something that all cities should welcome.

The One Southdale Place apartments located next to Southdale Mall.

Among the neighbors who spoke at public city meetings, Julie Chamberlain said,

“For the sake of 32 affordable housing units, are you really going to pass [the proposal] that sacrifices the integrity of the neighborhood and impacts 100 or more people that are sitting here today and hundreds more that couldn’t make it here this evening. For 32 units, you’re going to do that?” (Hankey, 2014). She also asked for a proposal that “better fits Edina” (Hankey, 2014).

When I first read this, I was honestly offended. It is not right for Chamberlain to speak for “hundreds” of people she does not know and to objectify low-income households as “units.” Her use of the word “sacrifices” portrays affordable housing as something bothersome to other families, when in actuality, low-income households are in need of the most help. It seems to me that Chamberlain does not understand that affordable housing can empower low-income families and lift them up to a quality life. Perhaps, her comment that affordable housing does not fit Edina may be from the perception that low-income families tend to be non-Caucasian. If this were true, her disapproval of affordable housing in Edina stems from personal resentment toward poor people of color.

Other residents accused the City Council of not following Edina’s own building guidelines when they should. One resident asked, “What’s wrong with you guys?” (Hankey, 2014). In response to the residents’ complaints, Mayor James Hovland reminded the City Council that successful developments like the Westin Edina Galleria violated the city’s building guidelines but ended up becoming an asset (Groessel, 2015). Eight-year Edina City Council member Joni Bennett added that this was the most residential support for Edina’s building guidelines she had ever seen (Hankey, 2014).

The Westin hotel located next to the Galleria in Edina.

In addition, there was no objection from Edina residents to developments of similar size in the Southdale area. Just across the street from the Boisclair proposal, Byerly’s Corporation is constructing the 71 France apartments, a trio of six- and seven-story buildings with 234 housing units—42 more units than the Boisclair proposal—which would also bring more traffic to France Avenue (City of Edina, 2015). Although the proposal easily surpassed Edina’s four-story height limit, there was no official opposition, so the apartment was approved for construction (Hankey, 2014). The main difference between the Boisclair proposal and the Byerly’s project is that one includes affordable housing while the other does not.

In my opinion, these Edina residents exhausted all possible arguments in order to avoid pointing out the elephant in the room: they do not want low-income housing in Edina, especially in their own backyard. I believe the majority of the protests do not give enough meaningful reason to deny the proposal. The value of making affordable housing available in Edina and its positive impact on low-income households is much greater than the trade-off between a five-story or four-story building, or more cars on France Avenue. As this article went into press, the 7200 France proposal decision has been extended to April 7th. Even in the face of intimidation from angry residents, the City Council must evaluate the proposal as objectively as possible while keeping in mind its potentially far-reaching impact on low-income families.

In another development, the Edina Community Lutheran Church (ECLC) proposed a two-story homeless shelter of 39 units at 66 West, adjacent to the Southdale medical district (Miller, 2014). The shelter would support homeless adults in their early twenties until they could afford independent housing and maintain a steady income (Miller, 2014). However, nearby Edina residents and property owners relayed their concerns to the City Council, stating that the shelter may increase “crime, illegal drugs and decrease homeowners’ property values” (Smith, 2014). Nearby Edina medical business owners also started a lawsuit to impede the shelter’s construction due to potential safety threats and building guideline violations, among other reasons.

It is important to note that strong opposition to affordable housing often stems from classism, racial prejudice, and false notions of affordable housing residents. In a 2012 national survey, Professor Rosie Tighe found strong, statistically significant evidence that those with anti-poverty and anti-minority attitudes also held negative perceptions of affordable housing (p. 15-16). Also, the respondents’ opposition to affordable housing increased as proposed projects moved from their “‘city or town’ to ‘neighborhood’” (Tighe, p. 10, 2012). This is called the “Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY) attitude, in which there is general support for affordable housing and its goals, but most people do not want to see it near their homes (Tighe, p. 2, 2012).

NIMBY attitudes are in part due to fears of increased crime, lowered property value, and higher taxes as a result of having low-income neighbors. However, a study in New Jersey found no correlation between affordable housing and those consequences (Albright, Derickson, Massey, Abstract, 2013). An additional study in New York also found that affordable housing neither increases nor decreases crime (Lens, 2013), so these are unwarranted prejudices against low-income people.

Thus, the crime, safety, and property value worries surrounding the 66 West proposal are baseless. The lawsuit also brought up Edina building guideline violations as a reason to deny the shelter; specifically, the business owners complained that the shelter did not fit in with the medical district, and that it violates the maximum number of parking spaces and minimum lot size (Kaczke, 2014). However, the lawsuit was quickly dismissed on February 12th, allowing the shelter to follow through with its construction plans (Groessel, 2015).

In sum, both 7200 France and 66 West projects were met with reactionary responses. In their battle against number-specific and technical issues, the protesters may have forgotten the true purpose of low-income housing: to break the cycle of poverty for individuals so that they may become self-sufficient. Before the 7200 France decision was extended, Mayor Hovland pointed at the real issue at stake:

“I think we tried to address all of these concerns that people have… But I think we’re making a real mistake in thinking about what’s the best use of that property by not embracing this idea of housing and affordable housing subsumed within it and approving this project [7200 France]. I think it would have been a great project for the neighborhood” (Groessel, 2015).

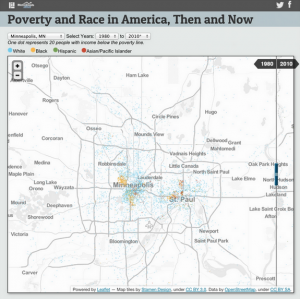

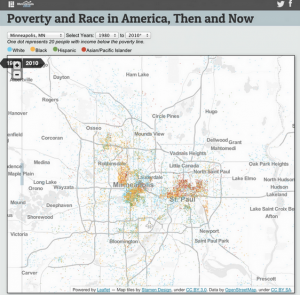

These affordable housing proposals would benefit all of the Twin Cities metro as well. Currently within the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, low-income families are being concentrated in neighborhoods segregated by race and income level. In this Urban Institute map of 1980, non-Caucasians and Caucasians living under the poverty line are concentrated together in the Twin Cities.

In 2010, they were still clustered in inner-city neighborhoods, but were largely segregated by race.

In 2010, they were still clustered in inner-city neighborhoods, but were largely segregated by race.

According to a 2013 Harvard-Berkeley study (Chetty, Hendren, Kline, Saez, p. 2) on income mobility, those who live in racially segregated neighborhoods where low income individuals are also residentially segregated from middle income individuals, rates of upward mobility are significantly lower. The study also found higher rates of upward mobility in areas with quality elementary schools and high schools (as cited in Leonhardt, 2013). In order to slow widening income inequalities, the Minnesota state government passed a successful law in 1971 – the only of its kind in the U.S. The law mandated all cities in the Twin Cities Metro to contribute about half of their commercial tax revenue into a collective pool, which would be redistributed to tax-poor communities to fund public social services, such as schools (Thompson, 2015). This law, known as fiscal equalization, helps low-income children graduate from higher quality public schools, which qualified them for middle income jobs, and as a whole, lessens the wealth gap between poor and wealthy suburbs.

Another law unique to Minnesota legally requires affordable housing to be evenly distributed throughout the Twin Cities metro, including wealthy neighborhoods (Thompson, 2015). Although this policy was highly enforced and was able to achieve many of its goals then, its governance has since greatly deteriorated. As seen with the two proposals in Edina, local city councils must grapple with disapproving residents. As a result, affordable housing projects have nowhere to turn to but back to the confines of already poor neighborhoods where chances of income mobility for residents are the lowest.

Growing poverty is inevitable as the population increases in the Metro, but we can slow it down. With continued enforcement of fiscal equalization and greater commitment to diversified affordable housing, Edina and other tony suburbs can do its part to break up poverty hubs. This won’t be easy though. Since 1996, Edina has only approved 11 units of affordable housing (Miller, 2014). Considering that, the city’s plan of adding 212 affordable housing units by 2020 looks quite unfeasible – but nothing is impossible. We can start by educating ourselves and our neighbors about the importance of affordable housing and by demystifying the false notions associated with low-income families. This will help us overcome a history of residential exclusion in Edina and accept people who are different from us.

Albeit, it would be a lie to say that I am not proud to be from Edina. I am always impressed by our prime education and my talented classmates, let alone our safe neighborhoods and burgeoning shopping centers. But we need to pop this perfect bubble we live in to face the fact that change is inevitable, and we need to embrace it. Together, we can create a community that uplifts all people – no matter how rich or poor. My hope is that these recent affordable housing proposals will encourage further opportunities in Edina, because low-income households need the education and employment available to us everyday. It is only right for the privileged to share what they have with the underserved.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions shared in this article are those of the writer, and not Zephyrus as a whole.

Annika “ika” Kieper, junior Zephyrite photographer, is excited for the upcoming school year . She wishes she could have an invisibility superpower,...

Drew Davis decided that it would be pathetic to recycle his sophomore year bio a third time, so he wrote a new one. Drew is thrilled to be online editor...

Julie Chamberlain • Oct 25, 2015 at 10:20 pm

I just saw this article online and frankly feel like my words were taken out of context. The statements around the integrity of the neighborhood was not in referral to having affordable housing units. It was because affordable housing was causing the development to be larger than it should have been for the site- a 6 story complex next to single family homes. Increased traffic through the neighborhood, right next to an elementary school. The issue was not affordable housing-it was a proposal that was grossly oversized for the piece of land, and the only reason the developer gave was they needed more rentable units to offset the affordable housing. Perhaps next time the writer could have reached out and asked for clarification I my stance instead of assuming the worst.

Chris Bonvino • Mar 28, 2015 at 11:47 am

As a life long Edina resident I found this piece extremely well written but also felt the tacit implication that Julie Chamberlain’s opposition to affordable housing was based upon racism to be offensive. Many of us have concerns about how low income housing could affect our property values and neighborhoods and these concerns are not based upon racial intolerance.