Letter to the Editor: Convergence Insufficiency Impacting Learning

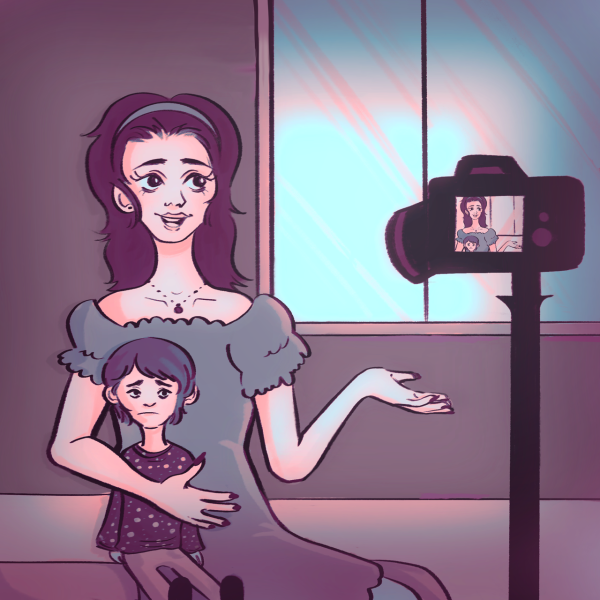

I am a retired high school teacher who recently earned K-12 reading certification, and became baffled this summer while attempting to assess an 11-year old girl’s reading issues. It turned out that she had convergence insufficiency. I want to share with you some critical information I have learned about children’s vision and reading, and ask for your help.

Fully 25% of children in kindergarten through sixth grade have vision problems severe enough to impact learning. Some of those problems are caught during routine vision screenings at school or in the doctor’s office. Most remain undiagnosed. According to the College of Optometrists in Vision Development, “Approximately 20% of the population has not developed adequate visual skills needed to function properly, especially when viewing small objects up close as required when reading print.”

Because the symptoms of uncorrected vision problems can look like Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder, some students are referred for special education. However, vision problems cannot be corrected through special education techniques. Others struggle along, falling behind their peers, often turning off to reading entirely. Because students believe they see the way everyone else does, they don’t report a vision problem to parents or teachers.

Mary McMains, O.D., M.Ed., F.C.O.V.D., wrote for Parents Active for Vision Education, “According to the California Department of Youth Authority, 70% of juvenile delinquents tested have vision problems affecting learning. When optometric vision therapy was performed on incarcerated youths, recidivism reduced from 45% to 16% at the Regional Youth Education Facility in San Bernardino, CA.” A Folsom Prison study found that 90% of prison inmates cannot read due to vision skills deficits.

Generally speaking, pediatricians and optometrists are not prepared to screen for these lesser known but widely experienced vision conditions. It takes a pediatric ophthalmologist or developmental optometrist to test for them and provide the therapy.

In 2013, when I earned K-12 Reading certification to become a reading specialist, the issue was never raised in the coursework. This reality affects me because recently I was embarrassed by not knowing how to address an 11-year-old private client’s reading problems differently from what already had been tried by her third, fourth, and fifth grade teachers. I am saddened, too, by the number of students I encountered who did not read for pleasure during my 33-year career as a high school English teacher, and surmise that many of them may have had unaddressed vision issues. I knew nothing about Congruence Insufficiency, Visual Motor Integration, Binocularity, and a host of other visual skills and deficits that affect reading. An informal survey of my former English department co-workers indicates I am not alone.

Imagine if 15-20% of women had breast cancer, but we didn’t screen for it. Unthinkable! Yet we let vast numbers of students turn off from reading, and struggle in school because information has not reached the right people to make a difference.

I am asking you to use your position as editors of Zephyrus to address the situation: educate students about the issue of undiagnosed vision problems. Encourage students to have their own vision checked by a developmental optometrist if they find reading tiring or uncomfortable, but they have been told they do not need glasses. Better yet, sign up for Mayo Clinic’s clinical trial on the most effective vision therapy for convergence insufficiency. Closing the “vision gap” may go a long way toward closing the reading/achievement gap.

Feel free to contact me about my ongoing effort to bring diagnosis and online therapy to Minnesota schools.

Sincerely,

Judy Layzell

Judy Layzell • Oct 21, 2017 at 1:13 pm

Thank you so much for having given exposure to this article. You used to record the number of hits, and it was well over 1000 a year ago, I believe. After my tenure at EPS ended, I doubled down on this issue. I am delighted to report that MDE followed up on my presentation, did their own research and worked with the legislature (and probably others) to mandate screening for convergence insufficiency. Districts must post their plans for all children to Read Well by 3rd Grade, including measures they will take to screen and identify students. At the end of the year districts will report numbers to MDE, thereby accumulating data to substantiate need and ultimately, I hope, lead to funding for treatment for the disorder. That legislation is in effect as of July 1, 2017, the same day that district literacy plans are due, making it possible that no written plan is yet in place. Fact Sheet: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwj95-eZp4LXAhWIwYMKHfTMCbIQFggoMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Feducation.state.mn.us%2Fmdeprod%2Fidcplg%3FIdcService%3DGET_FILE%26dDocName%3DMDE072236%26RevisionSelectionMethod%3DlatestReleased%26Rendition%3Dprimary&usg=AOvVaw24Jqk2OJ7jyc0TocWJNE5y

State Law: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=120b.12

Judy Layzell

Richfield, MN